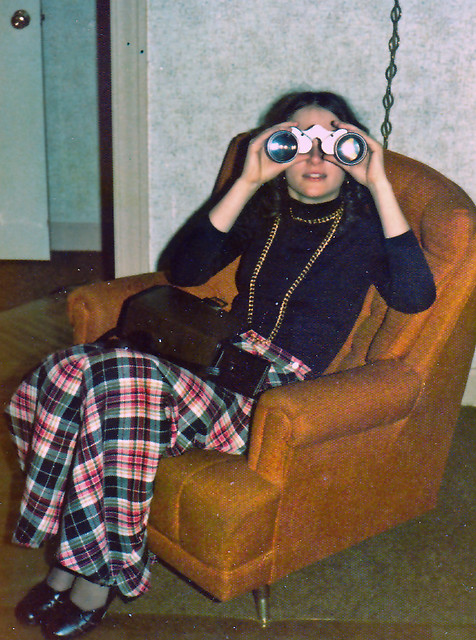

97. Don't leave home without binoculars.

Most birders take up the hobby after a particular bird somehow sparks their interest. But many people who are thrilled to see an unusually lovely or comical or interesting bird don’t know how to identify it or how to find another one like it. As I did on the day I saw dozens of lovely warblers in my maple tree as a little girl, they tuck the memory away and go on with their lives.

Many times when I’m watching a flock of warblers on a popular dog-walking path in a local park or a Snowy Owl on the ice near the Lake Superior shore through the window of a restaurant, people ask me what I’m looking at, and they often stop to look too. Once when I was walking in downtown Los Angeles, I heard some swifts chittering overhead and I wheeled to a stop and pulled out my binoculars. A man curled under some newspapers on a bus stop bench sat up and asked me what I was looking at. I said, “White-throated Swifts!” I then handed him my binoculars and he looked up with a confused expression. But the moment the swifts came into view, his face lit up. It reminded me of my own first memory of birds: As a little girl, I lived in an apartment in a tired old neighborhood in Chicago. I loved to kneel on the sofa, watch out the window, and wait for a drawbridge over the Chicago River to go up. Each time, pigeons flew up, higher and higher, drawing my eyes away from the grimy city and up to the big, beautiful sky. That memory came flooding back as I watched this homeless man looking up at a sky filled with White-throated Swifts.

When I’m checking out the Peregrine Falcon family nesting in a wooden box on a hotel in downtown Duluth, passersby often stop to ask me what I’m looking at. After I tell them, they almost always step up to my spotting scope to take a look. Peregrines are the fastest bird in the world and so are inherently interesting. The ones in Duluth have been nesting downtown for several years, but most people aren’t aware of them. Their delight when they see these birds is joyful to behold.

Once the conversation about the falcons begins, people often recount tales of birds they’ve seen in their yards, wondering what they might have been. I usually keep a field guide in my vest pocket, and when I pull it out and show them the possibilities, they are often surprised at how easy it is to identify a bird they’d wondered about for months. Many of them walk away saying that they’re going to buy binoculars and a field guide.

I started bringing my binoculars into restaurants as a security measure, scared that someone might steal them from my car. But I quickly discovered that having them with me is useful, since I always request a window seat. I’ve seen a Prothonotary Warbler out the window of a fast-food restaurant in Chicago; loons, mergansers, and migrating hawks out the window of a restaurant in Duluth; and a Snail Kite out the window of the Miccosukee Indian restaurant on the edge of Everglades National Park. As an added bonus, I’ve had the pleasure of sharing many of these birds with employees and other diners. When a major owl invasion brought birders from all over the world to Duluth, I found myself eating out with birding acquaintances who were in town for the fun. Wait staff were fascinated by this influx of birders, and because the owls were so conspicuous, they almost always had their own owl tales to share. This provided visiting birders with valuable information about good spots to check out, helped restaurant owners to see the value of birding to their own bottom line, and inspired at least a few restaurant employees to join the birding family.

Some birders are reluctant, from shyness or embarrassment, to walk around nonbirdy places with binoculars. But the practical benefits of sharing our hobby with nonbirders can be extraordinary. While living in Madison, Wisconsin, I used to go birding at a campus natural area every morning before heading to work. Picnic Point was technically closed until seven o’clock, but in spring I’d arrive well before six each day. One morning as I was scoping out some Hooded Mergansers in Lake Mendota, a policeman approached, almost certainly to kick me out, although I didn’t think about that until later. I was so excited watching the ducks with their comical headdress that I couldn’t help but exclaim, “Look! Hooded Mergansers! They’re displaying!” I stepped aside so that he could look through my spotting scope, and he was as delighted as I was. He said that he’d seen these birds during hunting season, but hadn’t realized that they were so beautiful in spring or had such an interesting breeding display. He didn’t kick me out, and after that, whenever he drove past, he would wave and ask what I’d been seeing.

Beyond the practical benefits to us, sharing our hobby with nonbirders helps business owners realize that birding is a hobby worth supporting, and it draws other people in. And the more people there are who support birding, the larger and stronger the culture of conservation and the support for bird preservation will be.

From 101 Ways to Help Birds, published by Stackpole in 2006. Please consider buying the book to show that there is a market for bird conservation books. (Photos, links, and updated information at the end of some entries are not from the book.)